I visited novelist and historian Lesley Downer at her home, to talk about how she became interested in Japan and about an array of fascinating women who have helped to shape Japanese history.

You’ll find a transcript of our conversation below, in case you’d like to skip ahead to something. And you can always listen to these interviews as a podcast if you prefer. You’ll find all the links you need HERE.

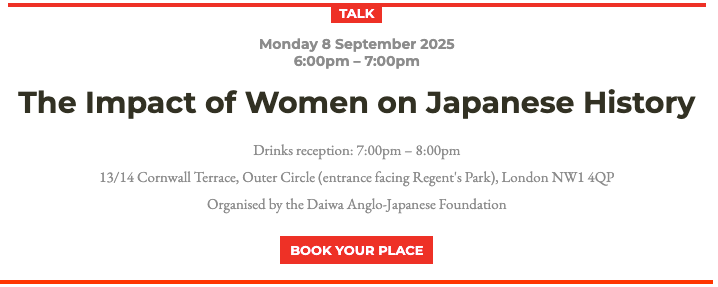

Lesley will be giving a talk about the impact of women on Japanese history at the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation in London on 8th September. You can book your place HERE.

Last thing before we get to the interview. If you haven’t yet taken my short poll about the kind of content that you most value in this newsletter, I’d really appreciate it if you could click HERE. It’s 3 questions, with no sign-in required.

Transcript

Chris (00:00) Lesley Downer is a historian and a novelist who specializes in Japan. We talked about what got her interested in the country and also about a series of extraordinary women who've wielded some serious power there down the centuries. So Lesley tell us a bit about yourself. How did you become interested in Japan?

Lesley (00:20) I come from an Asian background. My mum was Chinese, born in Canada. My dad was a lecturer in Chinese at SOAS, the School of Oriental Studies. So there was kind of Asia around me as I was growing up. There were books in Chinese stuffing my father's bookcase, which was every bit as jammed with books as I am now. He also had this volume that I've got now, 53 stages of the Tokaido. So I remember looking at that. And obviously when you're little, you think, Japan, China: same place. And then as I got older, I guess there were several things that directed me towards Japan, not China. One was China was kind of difficult to get to.

So that kind of cancelled out China for me. But also, so I was living in Oxford. I was making pots. I was very keen on pottery. And I read Bernard Leach's A Potter's Book, which is marvelous and is all about Japanese pottery. I'd been to India immediately after university for about six months. And I was desperate to get back.

I overheard various people talking about how you could make money in two places. One was Iran, one was Japan. And so I thought, aha, that could be a way to get back to India. And then a friend of mine was working at the Japanese embassy and he mentioned that there was a job available that being advertised in Japan. And that was what many years later became the JET Program to recruit non-Japanese speakers under the age of 30 to go and teach English in Japan in schools in universities, not language schools, and for these people to be English, not American, and for them to teach not in Tokyo but in the countryside. So there were three things.

Chris (01:57) of course to this day in a slightly changed form.

Lesley (02:01) That's the JET program, yeah. We were the first year, the absolute first year. It was 1978, was Gifu city, it was quite urban and they had asked me at the interview if I wanted to be in Tokyo or the countryside and I didn't realize that countryside meant anywhere that isn't Tokyo. So I thought I'd be somewhere, you know, with cows and sheep. Then I got myself moved to Sagiama which is more central in Gifu and I started doing things like I did tea ceremony, I did flower arrangement, I eventually did pottery, I did aikido, and I taught myself Japanese as quickly as I possibly could because there were no other Westerners in Gifu at that point.

Chris (02:39) So great for your language.

Lesley (02:41) I mean it was a sink or swim. It was sink or swim. Either I was going to have very stilted conversations in English. Most people, very few people spoke English and when they did they would ask me terribly boring questions about myself which was I was fed up with talking about why I was vegetarian and that sort of thing. So I learnt Japanese so I could be in control of the conversation. I'm a control freak.

Chris (03:04) at what point did you start to process Japan through the writing of novels? That's one of the things you're very well known for.

Lesley (03:11) That's quite a lot later on. I came back to England and I wrote nonfiction. Initially I did, I followed in the footsteps of Basho around the narrow road to the deep north. And that book has just been, has been reissued by Elan who are a travel publisher. So I'm rather pleased about that. I took Basho's walk around northern Japan, bit of up past Matsushima inland, past Obanazawa over to the Japan Sea coast down the other side. Yeah, I followed that route. And also in those days I would get myself a small book advance and then I would stretch that money out for as long as it would possibly last. So in other words, I took my time and I hitchhiked so it didn't cost very much and I stayed in minshuku. Actually most of the time I walked but when there was a long long distance and I would hitchhike.

Chris (03:58) Is it odd for people who pick you up? never sure whether Japan has or had then a hitchhiking culture in the way that the US has, for example.

Lesley (04:07) People were absolutely lovely. It may not have a hitchhiking culture, but everybody picked me up. And the other thing I did was I went to ⁓ motorway cafes, know, there's motorway places where people are all stopping for a cup of coffee and actually looked at people's number plates and could read the number plate. And so if someone's going to Kobe and I want to go to Gifu and I'm in Tokyo or something, I could go and say, excuse me, are you going to Gifu? Could you take me? Which I probably wouldn't dare do in anywhere except Japan.

It seems a bit kind of cheeky, but people were incredibly nice. And so I learned a lot of Japanese from traveling with these people. And there were lots of people that actually would say to me, so where are you staying tonight? Come home with us. And I'd go home with them. And I'd end up staying several nights because they were so nice.

Chris (04:50) What provoked that transition then from non-fiction into fiction? Which is quite a hard transition to make, is it?

Lesley (04:57) By that time I had written about Basho, I'd written about Geisha, I'd written about Sada Yacco, who was the model for Madame Butterfly. And particularly when I wrote the book about Sada Yacco, I tried to make that book come alive as much as possible, be as gripping as fiction. I decided to write about the Bakumatsu period, about the period between the arrival of Peri and the Meiji restoration. And I also thought it would be interesting to write about the Ooku about the Shogun's harem, if you like.

It's a harem in the sense that a harem is not all to do with sex, it's to do with a community of women. And the Shogun's Ooku was also to do with a community of women, with about 3,000 women in it, of whom some were concubines but not many. So I decided to write about that and then I decided to write about that, about the end of that, the fall of the whole system.

I think one thing about writing fiction is that at this stage, having spent something like probably 40 years odd, maybe more than 40 years, basically thinking about Japan, reading about Japan, being in Japan. There's a lot of detailed information in my head and also about the experience of being a woman in Japan. was, some fiction gave me the chance to flesh out material. I would do detail, I would look into what exactly would my heroine have worn and I'd also be imagining from my knowledge of having been with a lot of women in Japan and being a woman in Japan, how might she have felt at any particular moment. So imagining myself, taking myself, imagining in my imagination into Japan. What an adventure to do that. And what fun, it was great fun.

Chris (06:29) Do you find that we do tell the story of Japan, both of us who are historians, from with too much of a focus on the men? There's a balance needing to be redressed here.

Lesley (06:39) I mean men are obviously, men tend to be more active on the public front. Men tend to be more visible, so therefore it's inevitable that all the, you know, the prime ministers and the emperors and so on were men. I think there is a growing interest in women. In your books too, you mention a lot of women and tell a lot of women's stories, and there are women's stories to be told, which are interesting.

Chris (07:01) I thought what we could do is we could almost do a little mini tour through Japanese history with some of the highlights as far as you're concerned, some of the great women who've been part of that tapestry. Shall we sort of start at the beginning and go through? There some amazing characters. Shall we perhaps begin with Queen Himiko, this fantastically mysterious character?

Lesley (07:19) Himiko's name is the first person's name, not the first woman's name, it's the first person's name to come out of the mists of history. The first actual person. And she was, she lived about a hundred odd years after Bodica. But Bodica was like a warrior queen and Himiko was a shamaness or a shaman queen. So she had powers, but they were different sorts of powers. They were not warlike powers. And she was able to communicate with the gods and to ensure that the harvests would be good.

And she also brought peace. Japan had been a whole, it was a lot of warring kingdoms. And 30 of those kingdoms made a federation. And they thought the only way we're going to maintain peace is if we have a queen as opposed to a king on the throne. And she did maintain peace for 60 years. She ruled from the age of 20 to the age of 80. And she was not just a shaman she also wielded temporal power. She did keep herself hidden away as the emperor of Japan does to this day.

She had a spokesman, she had a thousand women to serve her and she had an army protecting her. It was a hierarchical society in which the low level bowed down to the higher level. People tattooed themselves as protection against dangerous fish and we can imagine how she looked because they have terracotta figurines dressed as she dressed in the clothes of the time which would have been the sort of clothes she would wear and we know that they grew mulberry leaves to feed silkworms.

So people have reconstructed, I've seen kind of reconstructions of the kind of garments you would have worn, a sort of tunic and a sort of skirt. And I think people also have found jewellery and they've found coronets.

Chris (08:57) And then there's talk that perhaps bronze bells and mirrors may have been part of this kind of ritual apparel. So she's absolutely fascinating. And I think there's still an argument over exactly where her kingdom might have been. I think different parts of Japan would like to attract some extra tourists. Did you have a favorite place where you think she might have been?

Lesley (09:15) Hashihaka which is tomb, is near Nara, as you know, and it is about the same date as she would have been, so it's quite possible it was her, so it could have been Nara. And the other choice, the favourite choice, is northern Kyushu, isn't it? And she was buried with, so according to the Chinese sources, with a hundred or possibly a thousand living attendants. But apparently archaeologists say that there wasn't any human sacrifice. I don't know how they, why they should say that, that's what they say. So maybe she was buried with these kind of terracotta figurines with some haniwa instead.

Chris (09:47) then I suppose if we fast forward a few centuries, we get to this period about which we probably know a lot more, the Heian period of Japanese history, so around 1000 CE. And I suppose for yourself as a writer, this is the source of one of those great Japanese novels, The Tale of Genji. If you could paint us a picture of life at the court in that period and who stands out for you as an interesting figure.

Lesley (10:11) like Sei Shonagan wrote her famous Pillow Book commenting on the incredibly ridiculous things that she saw and the sad things. One person I like is the unknown author of As I Crossed the Bridge of Dreams who never saw, she didn't see any men, she didn't actually have a husband ever, but she was actually, I think she was outside on her veranda with her friend at night when it was when it was possible to be there because the man couldn't see because it was night time and she had this conversation with the man and she fell in love with him with the sound of his voice and he was probably in love with her but she never got to see him again. were various mishaps and I find that unbelievably poignant. Poignant. And Murasaki Shikibu also had quite a poignant life. As you know, it wasn't even, it's not her actual name. We don't know what her name was and she's writing the tale of Genji which is this, in a way imagining this fabulous man, because she's probably not going to meet a fabulous man like that, who also had this kind of depth of tragedy, which makes him a very interesting character. And the fact that the men are all mixing perfumes and all having their different scents, and the women who have been only taught the kana syllabary so that they can read the sutras, are actually using it to write these really witty and cutting diaries and pillow books and so on. If the man comes in at dead of night to visit the lady so that she can't see his face.

And they are basically alone together, but there happen to be about 30 or 40 servants in the same room, but they don't count because they're not human beings. But they do know who the man is because they can tell by his perfume. mean, and that's, it's really amazing world. Also, of course, they're marvellous costumes. They're beautiful, 12-layer kimonos, their hair, know, trailing on the ground, glossy and black, the incense with which they sent their kimonos. It's a very aesthetically wonderful world.

Chris (12:08) This beautiful Heian period which you described so wonderfully, Japan seems to go through this transition where the imperial army in the Heian period and before it was a conscript army it often didn't fight very effectively, it wasn't a particularly glorious thing to be a soldier and then we get the rise of this famous samurai culture and I'm hoping you're going to tell us about Tomoe Gozen in a minute. How did she strike you, this fantastic female warrior and also

Is that a transition that Japan goes through from sophistication to not barbarity by any means, because some of these samurai were very sophisticated people, but nevertheless that sudden interest in martial value?

Lesley (12:47) It lasted 400 years, that Heian society, which is a long time. It's longer than we've lasted. mean 1625 to now, that's quite a long time, 400 years. But eventually the whole place was falling apart. And meanwhile there were various kind of uprisings, such as the Ezo who I'm rather fond of, who were the kind of wild men of the north, who were great horsemen. And the princely groups had been sent to the provinces. Their job was to fend off the Ezo but they also at some point decided, I think they came down to Kyoto and basically came in and took over and they had developed their prowess as samurai and they out in the provinces had developed those samurai ideals and those samurai skills and among them were women. It's more than just Tomoe Gozen but she's the most famous one. While The Tale of Genji is a novel, I think, and it's like Proust, like Jane Austen, it's very kind of delicate and all to do with feelings.

But later, the next period, we have epics, like the Tale of the Heike And she features there. And her story is rather marvellous, added to it, she was supposedly very beautiful. She had sort of white skin and long black hair and was a stupendous horse rider, could tame unbroken horses and could ride down cliffs. And her weapon of choice was, of course, the samurai woman's weapon, which is the naginata, which is the long-handled sword, which I suppose the nearest English equivalent is the halberd. But it's like a nine-foot long handle with a blade as sharp as a samurai sword, which are the best swords in the world at the end of it. And that is the samurai woman's sword. And throughout the ages, that was always the woman's weapon. So when your men folk are away at war and somebody comes and attacks your castle, you get out there with your womenfolk. I've also, as you possibly have, I've played around with the samurai sword too.

And I was, there's a swordsman I know who lives in Durham, who is called Colin, and he was trained in Kumamoto. He teaches the real swords. It's not Iaido it's real swordsmanship with real swords. And I had one go once and I stood there with my sword and he has a rolled up tatami mat in front of him, very tightly rolled, which is the texture of a human arm or human limb is very, very hard and you raise your sword up. And so I stood there with my left leg forward, my right leg back. And he said, if you stand like that, you'll cut your leg off. The blade is unbelievably sharp. So I then stood with my right leg forward, which is fine. So then the blade goes down like this. And as it went through this rolled up tatami, I felt no resistance of any sort whatsoever. It was like a knife through butter. It was Tomoe who drove the enemy. She had a troop of 300 warriors under her.

Her lover sent her out to be the leader of this troop and she drove the tyrant, who were the enemy, out of Kyoto and sent them fleeing to the west. And then there was then her lover decided that he wanted to take over and be shogun himself. Big mistake. So the shogun sent down Yoshitsune, who was the most famous warrior there's ever been and a huge army. And there was a huge battle at the end of which Tomoe and her lover, were only five men left. And so Kiso no Yoshinaka, her lover.

He said to her, you should flee and take my story back to the eastern provinces. And she, of course, being a great warrior, looked around for a worthy opponent. And then she was on her horse and she saw a poor chap called Honda no Morishige, who was the chieftain of the particular clan, grabbed him, pulled him off his horse, and held his head against the pommel of her saddle and cut it off. And then looked around to give the head, which is what you do with the head, to her lover. But his horse had become trapped in a paddy field and he was shot with arrows and was dead.

Chris (16:26) And as you say, then, so Japan after the Kamakura, well, during the Kamakura Shogunate and then afterwards the Muromachi Shogunate, this series of military governments that it has, before we get to the one that I think a lot of people have probably heard of, which is the Tokugawa Shogunate beginning in the 1600s, the right at the beginning of the 1600s. This is a period you know, I think, probably particularly well because both your non-fiction and your fiction, what, it's big question, but what are the various roles that women played in?

Lesley (16:54) Women had a lot of different roles. in the Tokugawa era, there were, I mean, the wives of the various warlords all played very different roles. And before the Tokugawa era also, one we were going to talk about was Nene, who was the power behind the throne, behind Hideyoshi, who was one of the earlier warlords, who was a warlord around the second half of the 1500s. Basically, we know a lot about her because the two exchanged such a lot of letters.

And she rose from being a low-ranking samurai to being first of all a daimyo in her own right because she ran the castle while he was away. And then she then reared the children who were not hers because she couldn't have children. And she also advised him. So he wrote her endless letters saying, literally saying things like, I'm on campaign in Kyushu. What do you advise? And he also wrote and said, I've taken this many heads and I've taken this many hostages. And tomorrow we're going into the field trying to think what the best tactics are. And she would answer and say, well, I think you should probably do this because

You know, the Shimazu were good at this, in order to get them right up, do this sneaky sort of attack. so she wielded a lot of influence backstage and also ran the show, which a lot of samurai women did while he was away. And one of her jobs as his wife was also to run the household of concubines. He had a lot of concubines. He had a hundred, though he was very fond of her, but he still had a hundred concubines.

And her job was to make sure that the concubines all behaved and didn't squabble, and also to take care of his mother, and also to deal with his favorite concubine, who was called Lady Yoda, who was the mother of his son and heir later on in life. But even though Lady Yoda was the mother of the son and heir, was still Nene's job to rear him. But then moving on, the Tokugawa period was 250 years of peace. So after the period of warfare, there were a lot of women who had lost their menfolk, and had lost their means of support, and had no choice but to live as courtesans or prostitutes. eventually they were, the way, the aim of the Tokugawa Shogunate was to establish order. There was no problem with sexual morality, no Judeo-Christian thing about sexual morality, but obviously you wanted order. And prostitutes and courtesans roaming around were disorderly. So the very first so-called pleasure quarter was established outside Kyoto in 1589, which is the rule of Hideyoshi.

And the idea was to have a small town a good size distance from the big city where it wouldn't pollute ordinary people. And the most famous of all these pleasure quarters was outside the capital which the Tokugawa Shoguns made for themselves, which was called Edo, which later, as you know, became Tokyo. Outside this capital, a fair distance up the river Sumida, so that people had to travel to get there, was the Yoshiwara, which was the most famous of the pleasure quarters. And that was home to about 3,000 courtesans and prostitutes.

And as Seidensticker once said, a day at the Yoshiwara was akin to an afternoon of tea. So Westerners who are very obsessed, Westerners are obsessed with sex, they always want to know about sex, but there was possibly not that much sex going on, partly because of value added, that if you are a grand courtesan, you don't take off your clothes for just any old Tom, Dick and Harry, far from it. In fact, maybe you don't take them off at all for anybody, which makes you all the more desirable. But they were professionals.

in their various arts, such as singing and dancing and music, and they also presided over salons. So while rich men might go there hoping they were going to get some sexual favors, poor artists and poets were welcome to come and attend the salons. And quite often the courtesan might bestow her favors on one of these poor, talented guys instead of on one of the rich guys. So there was a whole, the whole culture of that period, which, you know, think of woodblock prints, that comes out of the

of the pleasure quarters and literature like Saikaku's books. That's all about the pleasure quarters. In his case, I the Osaka pleasure quarters, know, lot of poetry. and the Kabuki theater was kind of like hand in hand. It was like the other side of the coin on the pleasure quarters. So the pleasure quarters was women who were banned from performing in public, but they could perform to private audiences. But the other side of the coin was Kabuki, which was men, adult men who were allowed to perform in public. And they perform a lot of the same things.

So this was not at all, not just a lot of sex, but a lot of showbiz. It was showbiz. And then, you know, something like 150 years after the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate, some of these women had, you know, were really into their particular chosen profession. And if they were going to be dancers, they were as great as the Bolshoi Ballet, you know, and if they were going to be singers, they were as professional as the Royal Opera House. And if they were going to be musicians, it was like the Royal Philharmonic.

They weren't amateurs and they realized that they did not have to sell their bodies at all. They could make a living as professionals with their arts and they called themselves arts people, which is geisha. Geisha. And then again, time moves on and young men about town realize that it's a lot cooler to be seen with a geisha than with a courtesan who's covered in makeup and has all his fancy clothes on. So a subtly dressed, understated geisha is the person to be seen with. And then when

The Westerners turn up. The Geisha are the trendsetters. And they're the ones who are trying out how he'll choose bustles and bonnets. And when dancing has to be done with ghastly, hairy Westerners, obviously men's upper-class wives don't want to have to do that. That's disgusting. But the Geisha will do it. Geisha will happily dance. They're not bothered. And they're used to being with all sorts of men, know, doing hairy ones. It doesn't really make any difference. And the other group of women who wield power.

I think would be the ladies of the shogun's household. And again, they're like Nene. There's his power behind the throne. So, you know, if you want a favor of the shogun or of the shogunate, the shogun could be a baby. They varied. But the thing to do is to find out who is his favorite. Either his mother could be his wet nurse, could be his favorite concubine, and to ply her with gifts. And that's the way to get your plea to the ear of the shogun.

Chris (23:06) So a huge amount of power in these various different ways. Some people would say that for some women at least, this is a period of real autonomy and real influence. Do you see, because you mentioned the Westerners turning up in the middle of the 18th century, a moment ago, after Commodore Matthew C. Perry turns up, you have this great opening to the West, Japan has this famously fast period of modernisation. All sorts of changes involved in that. What does it mean for women in Japan this period?

Lesley (23:33) 19th very early 20th, before the Jazz Age, not so great. I mean, in the Edo period, which is the preceding Shogunate period, at least there's one woman I know of. I don't know whether you can generalize to all women, but there's a very famous, she's been made famous because she's been studied. She was called Matsuo Taseko and she was a peasant. And, you know, she decided she was also a poetess. And she decided she wanted to go to Kyoto because she'd heard that was where poets gathered. And she simply said to her husband, well, I'm off.

And she went. So there's no kind of no control and her husband said that's fine. So he stayed at home and took care of the house and children and she went, she walked to Kyoto and there she actually ended up mingling with the shogun's ladies and writing poetry with them. And then she came home again and then she said to her husband, looks like things are happening in Edo. I think I'll go to Edo. Cheerio. And so she went again. But basically she didn't say, do you mind? I think even I would say, do you mind? I'm afraid I would. But she didn't.

Just went. And I don't know how many other women looked like that, but I'm under the impression that that wasn't so extraordinary, that men and women were not that, at that level, were not that radically different. ⁓ There were more constraints. I think the higher up in society, you get the more constraints. But the Meiji constitution said that women had to be good wives and wise mothers. They had to stay home and do the housework and take care of the children, which was actually not that great. So that was more constraining. The whole point of controlling Japan was to get it to a position where it could get rid of the pesky Westerners who would impose vile treaties on it. And so the idea was to prove to the Westerners that the Japanese were equal. That seemed to be the way to do it because the Westerners seemed to think Japanese were primitive. In fact, when I was studying Sada Yacco who lived around 1900, when she came and performed in England in 1900, she performed on the stage at the Criterion Piccadilly and the Coronet Notting Hill, and she performed various dramas.

And critics wrote, well, this is really extraordinary. We know Japanese are primitive, but this woman seems very sophisticated. How can that be? They wrote that in 1900. So obviously there was this belief that anywhere non-white was primitive. So the Japanese did their damnedest to prove that they were actually just like us and therefore we might clear off and leave them in peace. And by about the jazz age, they'd actually sort of done that. And the constraints were kind of lifted and a lot of people emerged.

And among these were people who were called moga, which stands for modan garu modan garu moga And they were flappers and they were bold. And a lot of these women had jobs, maybe elevator attendants, maybe florists, maybe beauticians, maybe secretaries, maybe journalists, maybe writers. There were writers among them as well. And they also, they were smoking. They were practicing free love. This is the women. They were discussing Marxism, anarchism, socialism, all those things people want desperately to discuss and it gets squashed again and again. But right then it was called the age of speed, sport and sex. They were eating ice cream, they were watching movies and Charlie Chaplin might have gone around that time, and Anna Pavlova. It was a really kind of, this was around World War I and it was a really great time for Japan. So that was women at that age. That was really, that was a moment of incredible freedom actually.

Chris (26:54) has this period of authoritarian politics, the military and politics, everybody then knows about the road to World War II and the conflict. And then after that it seems as though for women in Japan there's yet another chance to change their prospects, I suppose, with the Allied occupation mainly run by the Americans. They want to remake Japan, so pretty much in America's image. You'd have thought that might possibly work out well for women, but what's your view?

Lesley (27:18) It should bring about woman's suffrage and that was needed. I mean, I was there in 1978. That was when I was first there. And I didn't actually feel as I didn't think Japanese women had a bad life at all. I thought they had quite a reasonable life. mean, a lot of I taught Japanese women English and they seem to have a lot of freedom all day long. And their husbands were out at work, which they thought was great. And sometimes the husbands were actually away for sort of months, some ages, you know, on end. They also thought that was great. And the husbands, of course, the salary came to the wife who then

She made decisions about what car to buy, what school to send little Taro to, or whatever. So they were pretty autonomous. the ones I taught, this was in Gifu it was not. It was fairly typical in a way. They weren't particularly well-off, but they were well-off enough. And that was one of the things also that some of the prime ministers realized when there was, after the war, was a lot of kind of, a lot of ferment, a lot of people were very keen on Marxism yet again. But the final ploy was make everybody well-off, make sure everybody has a TV, a washing machine and a fridge. The three treasures, wasn't it? Yeah. And so when I was there, everyone did seem quite well off. The men were working very hard trying to make a living for their wives. And then they'd come home. These are talking from personal experience. They'd come home and they'd be really drunk. So I'd be visiting a woman friend and the husband, first of all, the husbands were kind of not nearly as kind of broad minded as the women.

So I'd go and visit a friend. And then the husband turns up who I've never met before, although I've known this friend for months and months and maybe years. And the husband would get on the phone and say, guess what? We've got a foreigner in our house. And the wife would look, you know, they go, you know, they're there, dear, you know. And then sometimes the husband would keel over completely drunk and land on the floor. And the wife would just laugh and we'd carry on chatting. So the husbands were not as liberated at all as the wives. I'm not saying they were liberated as such, but they seemed to have decent lives, women of all different classes of society that I came across.

Chris (29:22) You've been back to Japan many times, of course, since then. As a final question for you, the position of women in Japan now, I think often in the English language media anyway, are constantly saying how Japan ranks very low down in terms of the number of women in boardrooms, there's a general sense of autonomy for women. And I suppose some of these freedoms from what you said of the history are obviously being, are often being wielded behind the scenes or in various kind of quiet, subtle ways. And so we shouldn't assume that just whatever the most powerful and whatever noises men are up to is the extent of what's really going on.

Lesley (30:02) But that's also what men do. I men like to be kind of noisy. But like, I mean, when I was writing about geisha, you I went to, I mean, I heard of lots of geisha who are the geisha of the most powerful men in Japan. And the most powerful man in Japan, you know, might ask his geisha what to do, just as Hideyoshi asked his wife Nene what to do. So, you know, I went to one geisha house, one geisha house, one restaurant, and I was being entertained in this room.

and they said, you you have to stay in here for a while because the prime minister's in the next room, you'll be leaving. So the prime minister came and escorted by lots of gays. Of course, I just heard this, I didn't get to see it. But this turned out this was that particular prime minister's favorite place. It was in Shimbashi. And I think there's a lot of stuff that goes on in private that we don't know about. And indeed, why should we know about it? But also a lot of, you know, maybe through recent history, there've been a lot of very sharp women.

Geisha who have put thoughts into ministers or prime ministers heads. There's a lot of discussion. I don't know if there is still, but there always used to be a lot of discussion about so and so appears to be the man at the top. But who really wields the power? is, you know, there's just who's the person behind the kuromaku behind the gray curtain, black curtain. And then who's the guy behind that guy? And who is the person? Maybe it's a woman behind that person. Just because it looks like, you know, this guy is the prime minister. That doesn't mean he's got the power.

Chris (31:33) That was a lovely note on which to end, Lesley. Thank you very much indeed.

Very interesting. I will be teaching a course on "Notable Women in Japanese History" this fall, but my list is very personal and idiosyncratic. I presume every historian of Japan will have a different list.

Such an insightful conversation - so often in history there are incredibly influential women wielding power behind the scenes (and they often go unnoticed or uncredited). Great to learn about this from a Japanese history context as well. Thanks for sharing!