If you’ve lived any length of time in a foreign country, chances are at some point you’ve faced the ugly beast that is homesickness combined with culture shock.

For me, getting used to living in Japan, I found that it came in waves.

One day, I’d fancy myself to be having a reasonably fluent discussion with someone in Japanese, in an izakaya (basically a pub). The next, I’d be struggling to make myself understood while ordering in McDonalds. Or else complimenting a friend on the lunch she’d just cooked for me, blissfully unaware of how similar ranchi (lunch) and ranshi (ovum) sound to a Japanese ear, if a bumbling foreigner doesn’t take care.

‘Thank you for allowing me to eat your very tasty ovum.’ I’m lucky she didn’t call the police.

Dear reader, you surely have stories like these. That is what the comments section is for - so don’t be shy!

On a bad day, it can be something small and simple that pushes you over the edge. In my case, on more than one occasion, that thing was very small and very simple indeed: sandwiches.

Too tired and weary to face the complex ritual that is unwrapping an onigiri rice ball in the correct order - one mistake with those thin sheets of plastic and you’re picking your ranchi up off the floor - I would head over to the sandwich section of a convenience store fridge... only to find that even a straightforward sandwich was too much to ask for.

The dreaded onigiri packaging - see what I mean?

Some of the sandwiches would have fillings inside that were unidentifiable to the untrained eye, and I didn’t know enough kanji to read the ingredients. With others, the fillings looked vaguely familiar but they came in a pack with only one slice of bread between each set of fillings. Why? WHY?

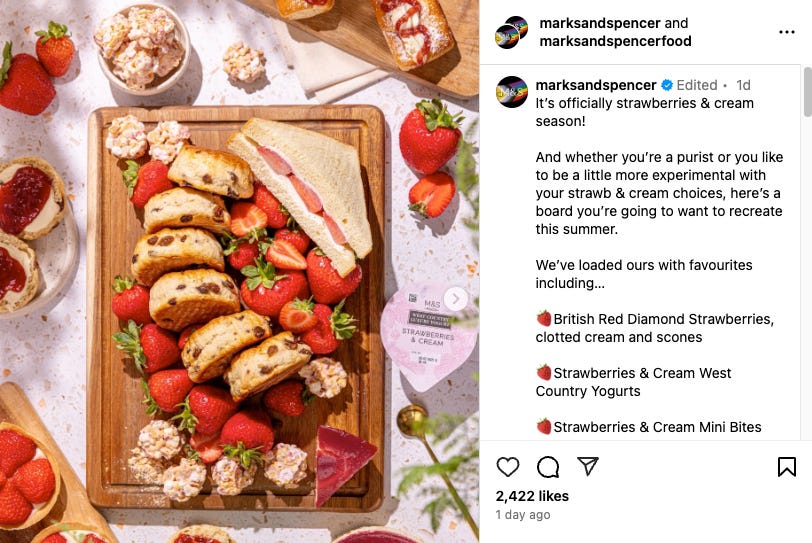

Without doubt the biggest offender, however, the thing that really gave me that ‘We’re-not-in-Kansas-anymore’ feeling about my beloved Japan was the sight of a sandwich with strawberries and cream inside it.

Had there been a robot rebellion at the factory where these sandwiches were made? Were human beings responsible, bored of their jobs and deciding to get a little art-house with their work?

I tell you all this because someone at Marks & Spencer has clearly been to Japan, seen one of these Franken-sandwiches and thought: ‘Yum - now why can’t we have those in the UK?’

Clean and plentiful public toilets? Agreed, we’d like some of those please, if we’re going to be learning from Japan.

Punctual and peaceful public transport? Again, yes please.

But, really, who was crying out for strawberries and cream between two slices of bread?

And yet - it seems to have worked. As someone at the Liverpool Echo put it, M&S has created a ‘viral sandwich.’ Which makes it sound like it’s in the news for all the wrong reasons. But no, the great British public apparently likes the idea, cleverly rolled out to coincide with Wimbledon tennis fortnight.

In the spirit of ‘know your enemy,’ let’s have a look at where the strawberry sandwich comes from.

European-style leavened bread entered Japan along with guns, cake and Christianity back in the early modern era, courtesy of the Portuguese. Guns very much caught on, quickly raising the noise level and bodycount on Japanese battlefields. Cake, in the form of Nagasaki Castella, has been appreciated for centuries: its most famous Japanese maker, Fukusaya, celebrated four hundred years in business last year. Christianity has had its ups, downs and occasional persecutions.

Bread, however, and with it whatever the Portuguese called a sandwich before the Earl of Sandwich came along in the 18th century (famously demanding his valet bring him beef between slices of bread so that he could eat while gambling), seems not to have caught on. The Japanese word for bread, pan, comes from the Portuguese word pão. But rice remained Japan’s staple right down to modern times.

I suspect that the Earl of Sandwich might have approved of what happened next. The Japanese of 1899 were not, as a rule, compulsive gamblers, but they were compulsive. Compulsive workers. Compulsive nation-builders. Compulsive competitors in a modern, globalising world where westerners seemed to hold most of the cards.

It was to these Japanese, of 1899, that an entrepreneur named Tomioka Shuzo served up what some claim were the country’s first modern sandwiches: an easy meal that could be bought at a train station and eaten on a train - a basic form of multi-tasking for busy people. Tomioka’s friend Kuroda Kiyotaka had fought the British in the Anglo-Satsuma War of 1863. But Kuroda ended up, as it were, eating their lunch: becoming a fan of the sandwiches that he encountered during his later travels abroad. He also became Japan’s second Prime Minister.

Fukusaya’s castella: moist sponge cake with a caramelised glaze on top.

So Kuroda introduced sandwiches to Tomioka, and Tomioka introduced them to the commuting public as a form of ekiben (literally ‘train station lunchbox’). A couple of decades later, a Kobe-based bakery started producing shokupan (‘bread for eating’): lovely loaves of soft white bread.

It was around this time that in especially cosmopolitan parts of Japan, including Tokyo and Osaka, fruit parlours and bakeries were opening up, heavily influenced by British tea and French patisserie culture. Quite where British food culture ended and French food culture began either wasn’t always clear or didn’t really matter. They were all Europeans, so why not mix a French cake with a British sandwich? In this way, the furūtsu sando (fruit sandwich) was born.

During the Allied Occupation after World War II, with many Japanese left hungry by food shortages, the United States began importing wheat flour into Japan in huge quantities. Schools began offering bread as a staple, and then in the 1960s bakers started to use milk and butter from Hokkaidō in their bread recipes. The Yudane method was developed, to help with moisture and texture: flour would be mixed with boiling water to form a thick paste, which would then be cooled and incorporated into the final dough.

Consumer culture never stands still in Japan. Those early, pre-war ekiben had contained ham and cheese: a good, solid option, if a little dull. But as the Japanese economy grew, tastes evolved and the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games helped to spread the popularity of the humble sandwich, all sorts of options began to come onto the market. Go into a convenience store now and you’ll see breaded pork cutlet (katsu) sandwiches, egg sandwiches and - yes - an array of those ‘fruit sandwiches.’

Japan even has bread-based superheroes:

From left to right, you’re looking at Shokupanman, Anpanman and Karepanman: sliced ‘eating bread’, sweet red-bean paste bread and curry-bread. Anpanman seems here to have removed and given away part of his head to a hungry child - a ‘superpower’ that shocked and disgusted the first parents to encounter it, in the 1970s and 1980s, but helped children to fall in love with him.

For visitors to Japan, there are - as is the way with so much of Japan’s food culture - cheap-and-cheerful versions of the fruit sandwich and ridiculously high-end versions. Fans of the former can find sweet sandwiches in just about any convenience store. People wanting to fork out serious money for a slice of history can head to Sembikiya: the first western-style ‘fruit parlour’ in Japan, with roots stretching back to a fruit seller in the Tokugawa period.

But of course, for Brits heading to Japan, the furūtsu sando will now hold neither mystery nor fear. M&S have seen to that. Those who choose to set up home for a while in Japan will doubtless find other inspirations for their homesickness and culture shock. Please share yours in the comments below!

Left: a 7-Eleven ‘strawberry sandwich’. Right: Sembikiya’s more upscale offering.

—

Images:

Onigiri: matcha-jp.com (fair use).

Castella: Japan Travel (fair use).

Shokupanman, Anpanman, Karepanman: Metropolis (fair use).

7-Eleven sandwich: Grape Japan (fair use).

Sembikiya sandwich: Sembikiya (fair use).

A curry doughnut from a convenience store was the first food I ever bought in Japan. Like the strawberry sandwich, it feels very wrong but also very right. I doubt it will ever make it to M&S though.

The promise of a strawberry jam donut, only to discover it was red bean paste, caught me out again and again. Or there was the time I was delighted to discover rhubarb at a roadside stall, then after preparing a crumble I discovered it was some bitter vegetable. Finally in Turkey this time, the rustic looking jam bought as a gift that turned out to be for leg waxing.