Quick note: my new book, A Short History of Japan, is out now. You can listen to the Introduction for free HERE.

If you were in Japan, or into Japan, in the 1990s and 2000s, you’ll remember talk of the country’s lost decade(s) and their toll on young Japanese in particular. The media, in Japan and abroad, brimmed with catastrophizing categories and buzzwords to describe a generation who were mentally checking out of society:

Freeters drifting in casual, part-time employment.

Parasite singles: sponging off their parents while indulging a taste for high-end consumerism.

Hikikomori shut themselves away in their rooms for months, even years on end (at home we refer to my wife’s sanity-preserving alone-time from our children as Hikikomummy).

Niito, with origins in the British acronym NEET, were people not in education, employment or training.

Sōshokukei-danshi: ‘herbivorous men’, refining hobbies or personal grooming at the expense of relationships or work.

I may be doing someone a disservice, but I don’t recall any commentators at the time suggesting that when these young people grew up, they would contribution to a revolution in politics. If someone did, then good on them: it appears to be happening.

For anyone new to Japan’s politics, here’s the headline: up until recently, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) ruled the roost. Rarely out of power since its formation in 1955 - for reasons that I’ll explore in my next Occupation post, later this month - the LDP became synonymous with machine politics. It was well-organised and well-networked, clever at keeping its base happy. It served as an umbrella for a wide range of political views and policy positions. For most aspiring politicians in Japan, the question was not which party to join but which faction of the LDP to align yourself with.

That began to change in the 1990s, when the truly epic scale of corruption in the LDP combined with the end of Japan’s high-growth years to cause voters finally to lose patience. Even then, the LDP managed mostly to cling on to power, thanks to two things in particular: coalition agreements with Kōmeitō (a party originally affiliated with the Buddhist Sōka Gakkai organization) and the apparent desire of Japan’s opposition to emulate the People’s Front of Judaea scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

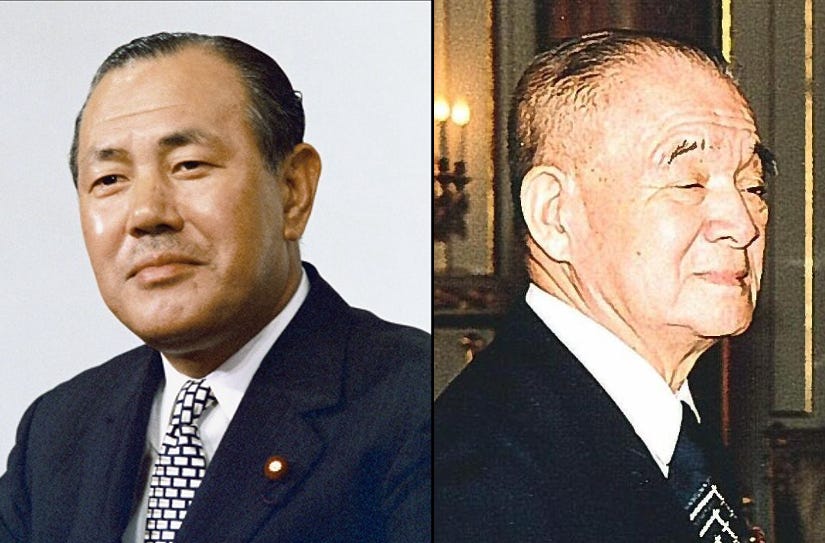

Former PM Tanaka Kakuei (left) and senior LDP figure Kanemaru (‘The Don’) Shin (right) infuriated the Japanese public when stories came out of enormous amounts of corrupt cash changing hands - sometimes from the backs of limousines, sometimes wheeled around in shopping trolleys…

The result was confusing and - dare I say? - a bit boring. Years ago, I would no more have developed a love of Japan based on its politics than I would based on - dare I say? - Japanese pop.

That is now changing.

For the first time ever, after this summer’s Upper House elections in Japan, the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition has a majority in neither the upper nor the lower house of Japan’s parliament. Prime Minister Ishiba has faced calls to resign, including from within his own LDP party. He is so far refusing.

So what’s going on in Japan?

The answer: more and more Japanese are deciding they have had enough of:

Stagnant wages

High taxes (your car alone costs you four separate kinds of tax: buying it, owning it, how heavy it is, and keeping it on the road - amounting to a higher tax burden on cars than in countries like the UK)

Expensive essentials, including rice

And - in some cases - foreigners

In my experience, xenophobia in Japan sometimes dovetails with a gentler, more understandable anxiety that non-Japanese people won’t know how to behave. The country’s famous omotenashi hospitality culture and high levels of social trust rely on people treating others with respect and kindness. It’s beautiful, and many western commentators wish for something like it. But it’s also fragile.

That sense of the fragility of Japan’s social contract is political dynamite: as a genuine voter concern and as something to which aspiring political parties can and do make powerful rhetorical appeal.

Who are these new parties?

Here’s where we get into the real story: the rise of two very different parties that could redefine Japanese politics. To keep reading, please consider signing up as a paid subscriber - or email me if you’d like a gift subscription for a month. You’ll find a short intro to my paid tier in last week’s post.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Japanese History with Chris Harding to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.