When someone or something pushes my buttons, I try - on a good day, at least - to stop and ask why. It happened last week when I stumbled across a Times column by Matthew Parris, bearing the headline: ‘Does anyone believe the promise of Paradise?’

I like Parris a lot. He’s witty and wise, and he writes with real humanity. All the more reason, I suppose, why this piece gave me pause - as did another of his on a similar subject, back in 2021: ‘Anglicanism was never really about God.’ Here’s a taste of the latter:

I don’t believe in God. But I love the Church, pay my subs to All Saints in Elton, sing hymns and delight in the Testaments Old and New. I say my prayers every night not because anyone is listening, but because I always have.

My first reaction was that this seemed like the worst of both worlds: godly duty without God. But of course that’s not what Parris meant. He makes clear elsewhere in these two pieces that like many others he loves ‘the fabric of the Church… the beauty, the ritual, the music.’ It’s just God, paradise, doctrine and all the rest that he can do without.

What gets me about this idea isn’t Parris’s views on religion - that’s up to him - or on Anglicanism: I grew up Catholic and haven’t spent much time in Anglican churches. It’s the sense of disconnect that Parris hints at, between Plato’s transcendentals: the Good, the True, the Beautiful. The sense that these three things each operate in their own, separate domains with nothing linking them together. They share no common grounding. There can be no joining the dots.

He might be right, but one of the reasons I first became interested in Asian history was that I hoped that those dots could be joined - and that perhaps, somewhere in Japanese or Indian religion, art or culture, they were.

I belatedly discovered a kindred spirit in the English philosopher Alan Watts (1915 - 1973). Where Matthew Parris derives great comfort from Anglican churches, Watts’ boyhood experience of Christianity was one of maudlin and incomprehensible hymnody combined with ‘quiet desperation’ homes, to which believers would return after a stint in some cold and joyless church.

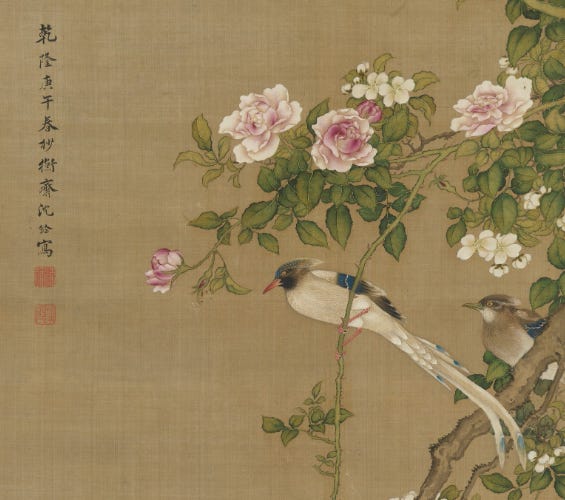

To his delight, Watts found that taking his time with Asian religion, philosophy and art revealed a divinity that was ‘immeasurably alive.’ He/she/it (Watts was never sure) shone through in ‘the eternal significance of momentary details’ captured in Chinese art: ‘the turn of a bird’s wing or the kiss of the wind on a particular blade of grass.’ This same sense of aliveness was there, too, in images of Shiva dancing and Krishna playing the flute.

Detail from Crabapple, China rose, and Indian Flycatcher (Shen Quan, 1750)

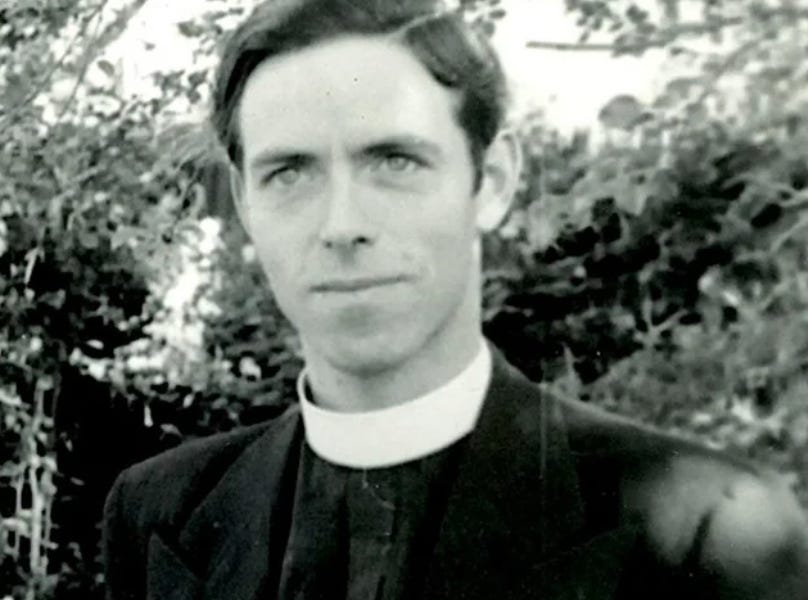

Given the unremittingly grim portrait that Watts painted of his childhood Christianity, it’s remarkable that before he shot to fame in the 1960s as a West Coast counter-culture guru and one of the great popularisers of Zen to the West, he spent a brief period, in the 1940s, as an Episcopalian priest.

He regarded himself, I think, as a kind of saviour figure, arriving from across the pond to liberate Americans from their toxic relationship with God. Their faith seemed to be one long round of ‘apologizing . . . asking [God] not to spank you, and telling him how great and glorious he is’ - alleviated only by whist drives, church bazaars and a ‘superficial effervescence of heartiness.’ Their churches were full of ‘courthouse furniture’ - stalls, pews, pulpits, lecterns - of a sort that screamed jurisprudence rather than religion. And their lives seemed weighed down by pride and an endless, doomed search for purpose.

Watts was sure that if Christians really knew the God of Asian art and religion, and understood the prodigal promises of their own faith, they would jump up out of their pews and start dancing in the aisles.

Critics of Watts view his decision to become a priest as a rather disingenuous attempt to find safe, institutional expression for his desire to be a religious and philosophical teacher. His sympathies, they say, were always with Buddhism and Taoism rather than Christianity.

But I think it’s hard to read works of his like Behold the Spirit (1947) and The Supreme Identity (1950) and not conclude that Watts was trying to do something real and precious: put together a renewed vision of Christianity, one that was capable of drawing together theology, radical social teaching, aesthetics, mysticism, history, poetry and cutting-edge science.

You can feel the excitement in Watts, in these books, as he discovers shared terrain between Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Taoism. One of the most significant discoveries for him - and for me, as a reader - was that they all possess concepts loosely akin to what Christians call ‘grace’: a sense that joining the dots between various aspects of human life, bringing together those transcendentals, is not a task to be completed by the intellect. It happens, mysteriously, in the heart and is only later ratified by the intellect.

Alan Watts in his priestly phase.

People in whom this happens end up becoming what Rowan Williams calls ‘witnesses’ for their faith. Sadly, Watts did not end up as one of them. As the disappointed publisher of his autobiography, In My Own Way (1972), discovered, for all his brilliance he remained more at ease performing his cleverness than probing his own depths.

I was thinking back to Watts this week not just because of what always strikes me as the pessimism of Matthew Parris when he writes about beauty and religion but also because of some interviews I encountered with the writer Lamorna Ash. She has just published a book: Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion.

Much is currently being made of the idea that Parris’s generation may come to be seen, in retrospect, as what you might call ‘spiritual inbetweeners’: sandwiched between the religious believers who preceded them and the believers who - against most people’s expectations - appear now to be emerging.

Lamorna Ash

Ash seems cautious about this thesis. But she speaks and writes with a kind of honesty and acuity about people’s religious explorations - hers and those of others - that is striking to me because it shows how important it is, in any effort to articulate where and how the Good, the True and the Beautiful may come together, to include the language of the personal.

I’m going to return to this in a post next month, exploring both Ash’s book and Abi Millar’s The Spirituality Gap - which charts her journeying far and wide, East and West, for something to replace the evangelical Christianity of her childhood. Both authors, I think, have something to tell us about how a younger generation are carrying on where the likes of Alan Watts left off.

But for now, let me leave you with Lamorna Ash, in conversation with Elizabeth Oldfield on The Sacred. Oldfield asked her to read out some lines from her book, on her early impressions of trying out prayer:

The version of myself who does the praying speaks from a truer place than I ever managed to in my day-to-day life, where I’m always trying to retain a kind of lightness…

There is nothing else like the utterances of prayer. It requires you to sift out what cannot or should not be prayed for, because you’re imagining yourself to be speaking towards something outside of the human realm, whether you believe in God or not…

Desire is healed in prayer because it is simultaneously outward and inward.

*

—

Images:

Detail from Crabapple, China rose, and Indian Flycatcher: The Met Museum (open access).

Alan Watts’ priestly interlude: Alan Watts reddit (fair use).

Lamorna Ash: author profile photograph (fair use).